Nobody’s Perfect

Characters, in all their shapes and forms, are what make or break a story. And the most beloved characters, the ones that stay with us the longest are often those whose halos are on slightly crooked. Small or big imperfections often act as a bridge in one’s understanding of a character – we see the way they’re flawed in the same way we see the way we’re flawed, with acceptance and a certain subconscious empathy.

What is often troubling about the handling of characters with flaws in moral-of-the-story type children’s books, is that we frequently find them being punished, ridiculed or chastised for their imperfections in order to drive home concepts of right and wrong. A good mother must be self-sacrificing, a good wife must be subservient to her husband who has to provide for his family etc., are therefore tropes that we retain because of frequent reiteration in books and from society at large. While these banalities are familiar to those who grew up with such books, they often fail to capture the brilliance of the grey areas between the black and whites – something that we, as people conscious of living in a flawed world, are so familiar with.

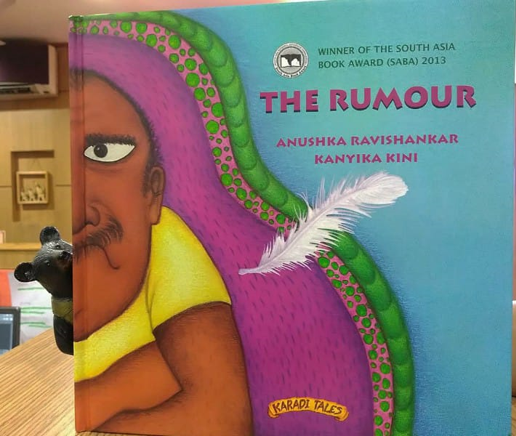

Story characters who remain calm and unruffled through entire story arcs are difficult to relate to and set unrealistic expectations for kids. We find it easy to identify with someone who is imperfect far more than we do with someone who is perfect. In the story of The Rumour by Anushka Ravishankar and Kanyika Kini, for example – it’s the entire village with an inherent character flaw. The villagers in the book are hopeless gossips. They cannot stop themselves from spreading rumours about Pandurang (the protagonist’s) little secret and their tales get taller and taller as they go from one villager to another.

The assumptions become increasingly fantastical before Pandurang’s story concludes. When it happens, it does so without standing in judgement of the villagers. The Rumour ends gleefully and with a levity that treats their character flaws with an off-handed acceptance. Kanyika Kini’s artwork in The Rumour is a perfect complement to the larger than life imagination of the villagers – they follow each rumour visually as they change, warp and grow bigger and more ludicrous with each passing spread. The earthy tones, the setting, the mostly profile drawings of the people and the interwoven verse all give The Rumour a fairly folktalesque quality – one that tells a tale of people with a fluid definition of truth and a lack of self-control with cheerful abandon.